Director: Richard Linklater

Stars: Margaret Qualley, Ethan Hawke, Andrew Scott

But for a marked purple patch in the middle of the last decade, it’s been business as usual for Richard Linklater of late, doggedly churning out movies at a regular clip, with quality ranging from the disappointing to the pretty decent. Blue Moon is his first of two being released in the UK within a matter of months. That’s just the way the cookie crumbles with this kind of work ethic. This time around both fall somewhere between biopic and historic curio, picking at moments of artistic arcana from the mid 20th century. Blue Moon takes us to New York on a March evening in 1943, for the rapt critical reception to Richard Rogers’ Broadway musical Oklahoma!.

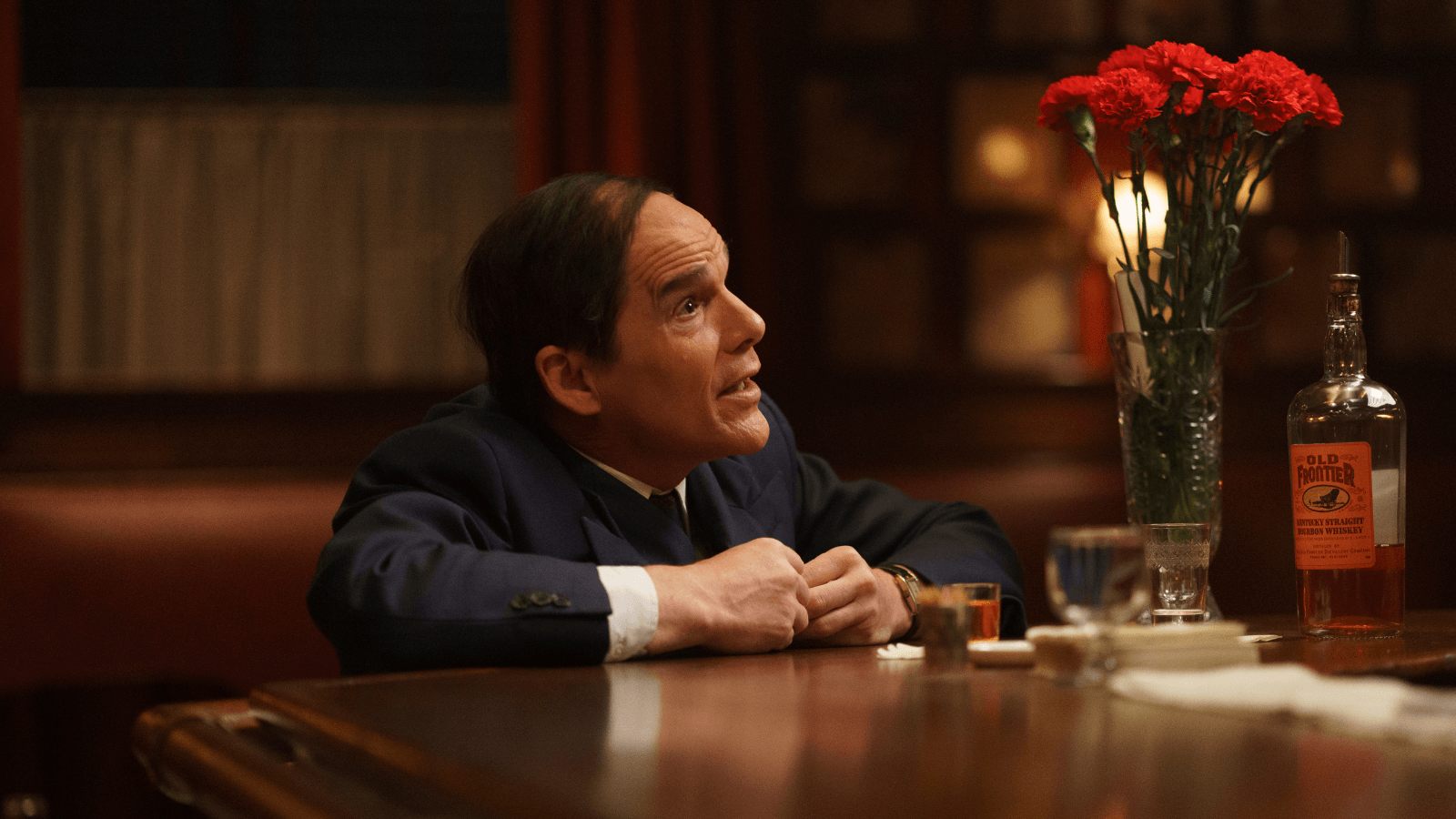

Rogers is not the subject of observation but rather his career collaborator (until recently, that is) Lorenz Hart (Ethan Hawke); a pithy, witty, alcoholic lyricist for whom the evening represents a particularly bittersweet commiseration. Capturing the man’s well-reputed and self-described ‘ambisexual’ nature, Hawkes both looks and gestures in a style that recalls, of all people, Ruth Gordon. Diminutive of stature but a veritable giant of verbosity, Lorenz holds court at a sparsely populated ground floor bar while awaiting the cavalcade from Broadway. Here he ‘performs’, propped up on a stool, a teetotaler cannily negotiating shots of whiskey from Eddie the bartender (Bobby Cannavale). Though his audience amounts to Eddie, squirrelled-away essayist E.B. White (Patrick Kennedy) and competent bar pianist Morty Rifkin (Jonah Lees), Lorenz soliloquises as though he has a full-house which, thanks to our attendance, he just might.

A single location chamber pierce that rests almost entirely on the writing and, by extension, performance, there’s little getting around how stagey Blue Moon is. Collated and given order and life by scribe Robert Kaplow from letters exchanged between Lorenz and his protege Elizabeth Weiland (Margaret Qualley) – half his age and with whom he is besotted – what unfurls almost always comes back to matters of adoration. From Kaplow and Linklater for the subject of their piece, from Lorenz to Elizabeth (whom, we sense, he knows full well is out of his grasp), but also between the artiste and the audience, as Blue Moon navigates the tussled over the no man’s land between mass appeal and intellectual rigor.

It’s a middle ground that Linklater has managed to negotiate for most of his career, rarely seeming pompous or pretentious in spite of the sometimes high-minded efforts that he’s taken upon himself to present. There’s remained a persistent everyman quality to his work that keeps it from appearing stuffily self-serious, and that easiness extends to Blue Moon. Its showiest aspects are the methods by which it sells Hawke as a good foot shorter than he actually is, and even these are rendered invisibly, through old school, in-camera methods, mostly.

The jostle between ‘one for them’ and ‘one for us’ comes to the fore once Rogers (Andrew Scott) arrives with an entourage of well-wishers and glad-handers (and one comically indiscreet young boy). Stealing Rogers from this throng of socialites, Lorenz pitches a preposterously ambitious 4-hour musical on the life of Marco Polo, quite clearly transposing his own present obsession with Elizabeth into the narrative. Eager to pry Rogers away from his new collaborator Oscar Hammerstein II (Simon Delaney), Lorenz’s cattily-clear disdain for Oklahoma! leads to a stairway argument that lightly interrogates the duties of an entertainer and the role the audience plays.

But the best is saved for last, as the third act sees Lorenz finally getting to spend time in the intimate presence of his beloved Elizabeth. Hawke and Qualley hunker down in a quiet backroom for a confessional that is by turns funny, heartbreaking and pitiable. In this late section the tragedy of a stolen heart is laid before the audience and the two actors – both on fine, fine form – have rarely been better.

Still, coming away from Blue Moon with it’s saucer-eyes for unrequited love, beauty and the poetry of the imagination, its smallness keeps it within a set of glass parentheses from which it can’t quite escape. Lorenz’s run-on style of auditory will charm as many as it alienates. Hawkes delivers it tremendously, with the largess of a performer commanding a theatre stage, but – for Lorenz – it is also exactly that; an outsized performance from a man with wounded pride who senses, correctly, that he’s on the downhill slope.

This is some handsome middle ground material from Linklater. Nothing near as wildly ambitious as the likes of Boyhood or A Scanner Darkly, but equally a more comfortable and cordial dip into showbiz apocrypha than, say, Me and Orson Welles. As much as Linklater is perpetually preoccupied with the passing of time (and this picture takes place, for the most part, in real time), so Blue Moon feels like a lament. Both for the golden age of Broadway and, for Lorenz personally, for relationships both past and in potentia that he sees disappearing like cigar smoke over an empty shot glass.

1 thought on “Review: Blue Moon”