Director: Emerald Fennell

Stars: Jacob Elordi, Margot Robbie, Martin Clunes

Although they don’t often make waves outside of certain circles, quite often you’ll find a notable auteur directing a short film to promote some fashion house or other, or luxury goods like motorcycles. A Nicolas Winding Refn perhaps, or a Luca Guadagnino. Even David Lynch in his time. Usually it is as you’d expect. A way to raise some capital. Something to help fund the next project. Emerald Fennell’s latest feature, however, simply feels like one of these silken designer ads blown up to 140 minutes.

Her empty shirt flutters high in the winds again, here reworking teenage memories of Emily Brontë’s dour literary classic into a tacky, abridged and shallow facsimile, promising hot, scandalous intensity but delivering only the immaterial byproduct of a marketing strategy. A film so weirdly connected to it’s own promotional facade that it opens with a joke at the audience’s expense. Is that the raunchy sound of sex play we hear? No, it’s a public hanging. Fennell’s all about reputation, it seems. But her cheeky wink to the viewer belies more truth about the presentation about to unfold than intended, and in the end it’s her film that swings lifeless in the breeze.

I almost didn’t bother with “Wuthering Heights” – those quotation marks belying a sense of hedged-bets at every turn – after truly hating her last effort, the desperate faux posturing of Saltburn. But, as with Wicked: For Good at the tail end of last year, it’s box office monopoly left nearly no other choice, despite numerous worthier-seeming movies lost to this one’s Goliath roll-out. Kudos to the strategists for whetting appetites and more over the past months. And while nominally an uptick in quality compared to Fennell’s last, the end product feels like nothing but a continuation of those efforts. The ChatGPT version of a literary classic.

I’m not precious with adaptation. One medium isn’t another, and playing freely with a text can yield creative, captivating results (see One Battle After Another and hundreds more). But it helps if the basic kernels of the source can still be distinguished. If it retains the spirit. Without those things, it can amount to dress-up. Fan-fiction. Fennell’s assertion that this is the story she remembers is valid. Memory has a way of distorting and promoting. But those precious about Heathcliff and Catherine may wish to brace themselves for a fairly loose interpretation.

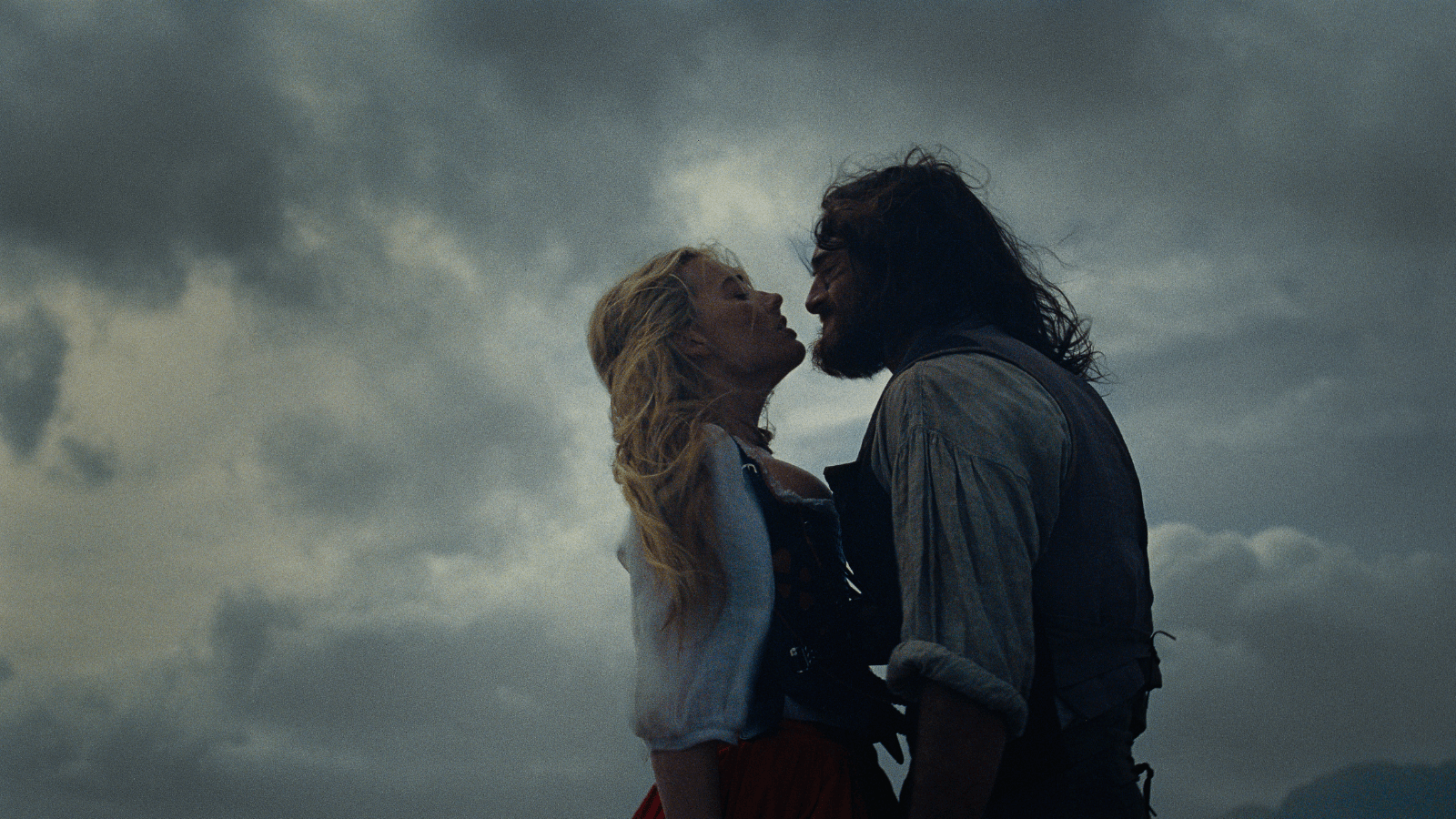

Taking place in a Yorkshire that’s mysteriously free of, you know, Yorkshiremen, “Wuthering Heights” tells of a semi-successful landowner named Earnshaw (Martin Clunes), living at the wind-battered estate of the story’s name with his daughter Catherine (Charlotte Mellington, later Margot Robbie). Earnshaw takes in a nameless gypsy boy who is given the moniker Heathcliff (Owen Cooper, later Jacob Elordi). Elordi’s casting has already proven contentious, as Brontë’s prose is precociously vague about the boy’s race and background. Catherine and Heathcliff are inseparable children, developing a fast bond. The novel’s psychological kismet between two damaged individuals is here reconstituted rather prosaically as one-note sexual attraction. As a coming-of-age odyssey, it works in a Mills & Boon sort of way. Elordi has something of Heathcliff’s dour demeanour, but his brutish indifference has been recalibrated as needy subservience. He is mopey. Heart-on-sleeve. Catherine, meanwhile, is drawn anew. Here she is prissy, vain, forever flouncing.

A misunderstanding perpetuated by Catherine’s watchful servant Nelly (Hong Chau) causes Heathcliff to flee, and sends Catherine into the arms of wealthy bachelor Edgar Linton (Shazad Latif) and the doolally interior designs of the lavish Thrushcross Grange. Years pass and Catherine yearns for Heathcliff. Festooned with riches, she is alone. But when he does reappear, emotions are stirred and quickly rekindled, albeit now shaded by the change of circumstance for all. Heathcliff has become rich, and he buys Wuthering Heights, where Earnshaw has rotted away, losing his modest fortune to gambling and alcohol.

Those already initiate with the tale may note that several characters have been whittled away, along with the book’s framing device as well as the last 100 pages or so (which most adaptations tend to do) and, by and large, these aspects aren’t wholly missed, though they do further the simplification of the material. Fennell shows some sense in narrowing focus. But in their place are banal provocations and withering dialogue (“Blue is blue no matter how small”), and she never passes on an opportunity to have her characters literally speak their feelings as exposition for the slow-witted or the disengaged. There’s zero nuance or inference to this vision. Everything has to be seen and said. It’s bold and maximalist, something made evident in the ‘extra’ interior design and costuming – as stifling and distracting as a Tim Burton movie. It’s lavish and absurd, and those things are enjoyable by themselves, but also feel like Fennell distracting herself with gaudy baubles.

The same might be said of Charli xcx’s much-promoted soundtrack of new songs, which pepper the film quite scantly. Actually, Charli’s album works well as a separate entity. She’s fully understood the assignment and produced a clipped set of Gothic bangers. But, like all the other drapery at Fennell’s disposal, they don’t coalesce with the story. They sit on top of the picture. More successful is the implementation of Olivia Chaney’s rendition of “Open Up The Dark Eyed Sailor”, which recurs in the film and at least feels attuned to the weather-beaten bleakness of the Yorkshire moors.

As events unfurl – a raunchy-if-unfulfilling montage here, a ridiculous Christmas there – some of Fennell’s dumbing down of the material grows irksome. Isabella (Alison Oliver), whom Heathcliff marries to spite Catherine, is a particular casualty, rendered here as a mawkish, snivelling caricature for audience mockery. It’s a troublesome decision as it complicates the abuse she ultimately suffers. Domestic violence becomes something of a misguided gag, okay so long as we’re told in no uncertain terms not to feel pity for the abused. It’s all as ornate and void of feeling as Isabella’s dollhouse. But, thanks to the half-hearted efforts to drum up the illusion of scandal (the walls of flesh, the fish-fingering, Isabella’s godawful Carry On-esque scrapbook), it’s so un-serious as to never court genuine offence. It is, at least, interestingly bad as opposed to just long.

Elordi’s roaming accent work sort of makes sense given the character. The girlification of Catherine is annoying, however, undeserving of a literary icon. It’s as though Fennell can’t quite see past Robbie’s Barbie. For those seeking a (somewhat misguided and compromised) windswept romance and the further codification of Elordi, it’ll sate certain needs and enable plentiful fantasies. There’s eye-candy here, and in the main this seems the sole concern. For anyone after something that captures the spirit of the source without simply taking it back off the shelf, stick to the impressionistic 2011 Andrea Arnold adaptation, or even PJ Harvey’s “Is This Desire?” LP.