Director: Zach Cregger

Stars: Julia Garner, Josh Brolin, Benedict Wong

With just two features under his belt now, there are a few things we know Zach Cregger has a preoccupation for. He has a thing for basements (Barbarian tipped that all on its own). He’s wary of a crone (could write a whole sub-piece about the recent resurgence of the terrifying elderly). And he likes playing the puppeteer; switching vantage points, moving his respective characters on a step or two, controlling the board from on high. Occasionally to his detriment this can mean that the characters themselves feel like a means to an end. A way of getting from point A to point B along the swiftest, most direct line. It’s ironic, then, that Weapons is all about puppets and puppeteering. About control and the illusion of it.

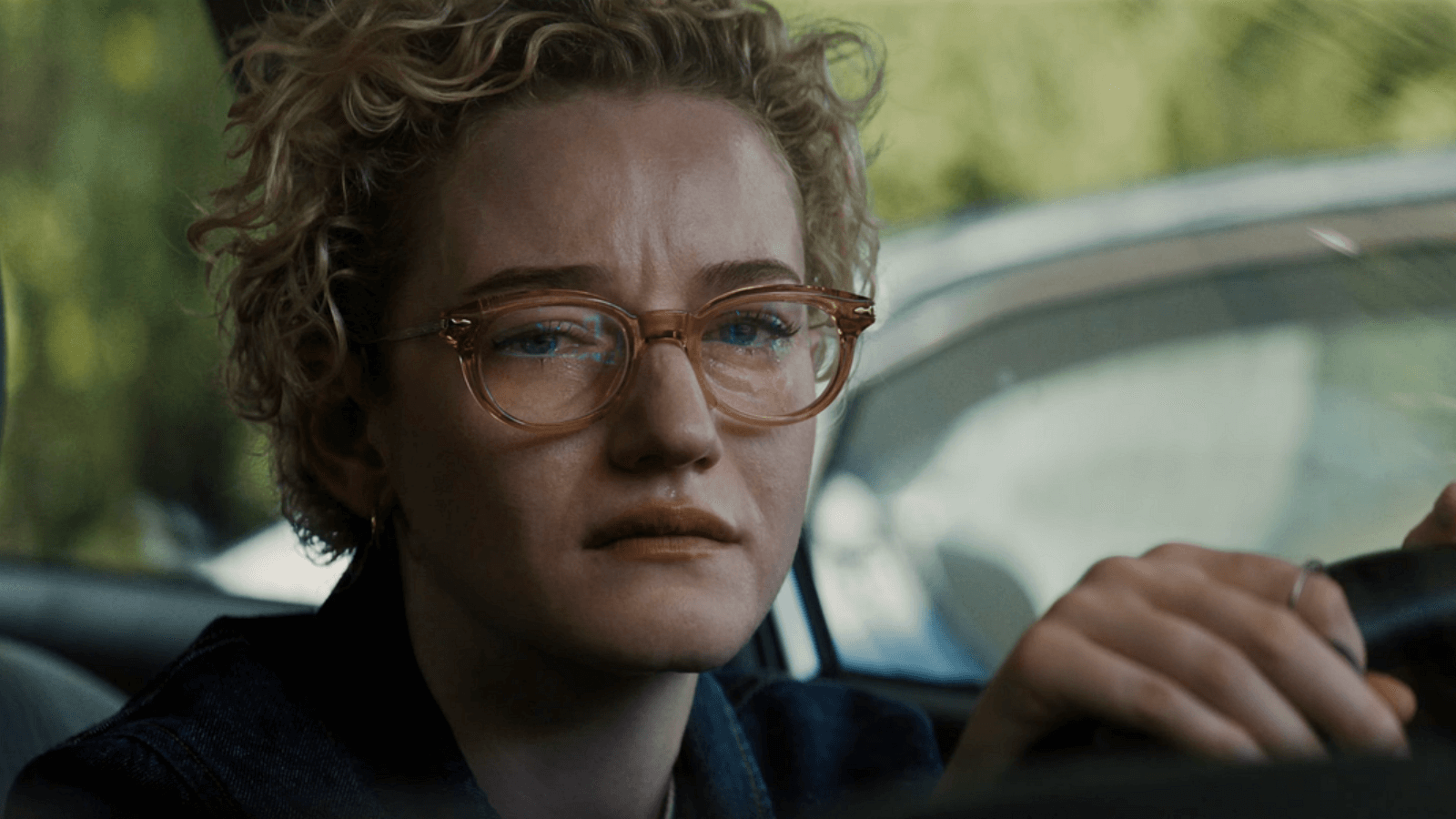

Set in the pleasant middle-American nowheresville of Maybrook, Weapons opens with some sing-song child narration advising that the unifying tragedy that locks its characters together has already happened. On an average Wednesday at 2:17 in the morning, an entire class of school children (bar one) disappeared into the night, seemingly of their own volition. All from the same class, those under the tutelage of functioning alcoholic Justine (Julia Garner). With the community reeling and, a month on, no closer to solving the mystery, Justine has become the de facto scapegoat. She’s hounded out of town meetings, daubed a “witch” by unseen vandals. But how this tragedy effects Justine is only one facet of the story, as Cregger sets up multiple chapters, passing the baton from person to person until we have the complete picture – something none of his characters ever manage to achieve. Only the god’s eye sees the whole.

While the film’s with Garner it is arguably at its strongest, though at this early stage the viewer is working under a number of assumptions. Through her experiences Weapons gives the impression of being an essay piece on communal trauma, working as a broad metaphor for any collective shock, be it COVID, a school shooting, you name it. HBO’s The Leftovers feels like a key touchstone. And this continues once we move on to Josh Brolin’s bereft father figure Archer, determined to play armchair detective, bullish but definitely onto something. The need to apportion blame for the mystifying or unthinkable glues these people together, whether they’re aggressor or victim (or both).

Cregger does enjoy playing ringmaster. Each of his chapters ends on a bizarre turn or discovery. A series of mini cliffhangers. One imagines him concocting this story piecemeal, feeling a thrill every time another element locked into place. The middle of the picture can feel like we’re being taken on a circuitous journey, however. Episodes in the company of Alden Ehenreich’s frustrated cop Paul or Austin Abrams’ wiry junkie James tip Weapons toward calamitous comedy and risk obfuscating our emotional connection to the conundrum. Fortunately they’re entertaining enough in their own right to keep us on side, but it does feel like we’ve strayed into more performative directorial territory. The realms of your Pulp Fictions or Strange Darlings.

If anything this is getting us ready for the film’s final mutation. It’s last and longest act takes the tale back to its roots. Where Barbarian inferred a lot of the exposition, Weapons goes to great lengths to explain. It may even have benefitted from trimming this back (by this point the savvy audience member will have connected most if not all of these dots already; walking through them as we near the 2 hour mark is a little testing). But patience is rewarded with a bout of extravagant catharsis unlike any to have played on cinema screens this year. The last ten minutes or so is a riot. Weapons confidently makes the jump from mournful parable to lunatic comedy with the zest and energy of a frazzled V/H/S short. Cregger takes a bow, beaming that he’s earned it.

It does feel a mite self-satisfied, and there is the sense that some of his characters live with various traits or conditions solely to manufacture the next plot convergence, making their struggles seem a little hollow. But the step up in ambition from Cregger here is fun to watch unfold. Weapons feels like a concerted effort to show he can sit at the big boys’ table (and, lo and behold, he’s landed a major IP for his next film). Thankfully it’s a little more than just a covering letter for a job interview. This yarn has clearly been Cregger’s own obsession for a while. An idea that’s preoccupied and grown, the compulsion to tell it far more important than how it’s received.

There are strong echoes of Stephen King here in the dissection of the American community and, in the late emerging villain of the piece, a feathering in of the vast country’s own folklore and dark past as a slaver’s nation. And, of course, our collective fear of clowns. If I’m getting vague it’s because I’m loath to spoil too many surprises. Suffice to say that if Garner and Brolin represent the emotional standouts, then Amy Madigan is operating on a register all of her own. She’ll become a horror legend for this. Weapons is far from perfect, but it is impressive in its construction and incredibly entertaining. It fizzes with ideas. And if some of them aren’t new – even to Cregger – his passion to communicate them with some form of originality ought to be recognised and appreciated.