Year: 1961

Director: Michelangelo Antonioni

Stars: Jeanne Moreau, Marcello Mastroianni, Monica Vitti

Being a bastion of great taste (ha), I’m currently in the midst of a re-watch of the prestigious AMC TV series Mad Men, and doing a sort of ad-hoc Mad Men film club along with it, watching some of the movies directly referenced by the show as it goes along. This has meant Psycho and The Apartment (both welcome revisits). As I push into season three, Bye Bye Birdie is the most recent to merit another look (and what a deranged spectacle that is). Michelangelo Antonioni’s La Notte is mentioned briefly during the second season as an example of sexy European cinema, but it’s a third season episode that more prominently recalls it.

The episode in question, for those who care, is 3×03 “My Old Kentucky Home”, which largely preoccupies itself with the various cast members’ extracurricular talents, finding ways to present them in a surreptitious variety show (Christina Hendricks playing the accordion; Vincent Kartheiser and Alison Brie doing the Charleston etc.). Many of these take place at a picturesque summer party hosted by the rich Roger Sterling (John Slattery), who embarrasses himself grotesquely with a minstrel show routine, crudely highlighting a cultural rift that came to define the ’60s (a sequence which itself feels like an echo of one that occurs in Antonioni’s L’Eclisse in which African tribal dance is uncomfortably appropriated). As ever with Mad Men there’s an undercurrent of malaise and ennui centred around adman Don (Jon Hamm), and the episode ends with Don and his pregnant wife Betty (January Jones) isolated on the verdant country park grounds, sharing a rare moment of unguarded intimacy in the gloaming of the encroaching night.

La Notte – the second in Antonioni’s landmark monochrome trilogy* of films confronting the alienation and isolation of the Italian bourgeoisie – is quite similarly structured, further evidencing its influence on Mad Men show runner Matthew Weiner.

Beginning with a stern descent down the outside of a modern skyscraper – all glass and steel, redolent of the modern, yet amnesiac visage of Italian urban development – La Notte opens with its central couple, Giovanni (Mastroianni) and Lidia (Moreau) paying a social visit to the hospital. They are there to visit Tommaso (Berhard Vicki), a mutual friend and peer of Giovanni’s and a terminal patient stricken by an unspoken malady. Giovanni, it transpires is a success. Newly published. But the framing and the editing suggest a schism between him and his wife; an unspoken tension that will become a more pronounced negative space in the film.

Antonioni was fascinated by these negative spaces in our lives. The unidentified rifts. The ways in which we isolate ourselves even in company. It’s there in the unsolved mystery at the heart of his prior film L’Avventura in which a holidaying young woman disappears inexplicably, never to return; it’s in the blocking of his subsequent feature L’Eclisse, in which he slices up frames with great concrete stanchions. And it’s there in the way both of those films become increasingly preoccupied with the still architecture that surrounds their respective characters, as though his protagonists have been annihilated or rendered redundant. Immaterial in the passive face of concrete and stone structures.

Giovanni flirts with marital oblivion while his wife weeps outside the hospital (we assume for Tommaso, but perhaps for herself…). He allows himself to be harangued – for the second time – by a nymphomaniac (Maria Pia Luzi) wandering unsupervised on the ward, indulging her advances recklessly before they are interrupted. It gives us an early insight into his character (or lack thereof). Antonioni frames the two of them in her hospital room against a blank wall. There are no reference points for the dimensions of the room. Just two figures lost in space. It accentuates their listlessness and the sense of entropy in the scene, but it’s also emotionally reminiscent of abstract expressionist work, like that of Rothko. An image designed to make you question how it makes you feel. Confessing the encounter to Lidia in the car after, Giovanni is shocked by her pragmatism and detachment; a mark of the gulf that has grown between them, only now registering.

Shortly thereafter Lidia has a mini-odyssey of her own, travelling on foot from the modern, revitalised districts of Milan to more downtrodden, poverty-ridden suburbs. She crumbles rusted iron in her fingers, encounters an abandoned child and, later, is aghast at young men brawling in a deserted lot. This is interspersed with scenes of Giovanni in their affluent high-rise apartment. While comfortable and well-furnished, it feels a little too like the hospital room we only recently escaped. Affluence as detachment portrayed through contrast.

That evening – seemingly only to escape the doldrums of another night in their apartment together – the couple attend a party hosted by millionaire acquaintance Gherardini (Vincenzo Corbella) (La Notte‘s equivalent of Roger Sterling’s country park soiree). Following a brief detour on the way to a boozy jazz club where the couple are entertained by a black dancer/gymnast contorting her body around a goblet of red wine (skilfully avoiding spilling a drop) the couple arrive at their destination.

Lidia is the first one to spot Monica Vitti’s bewitching Valentina, coming upon her in a moment of quiet, spying her from the vantage of the top of a staircase, the younger woman sitting at the bottom reading a book. In this moment it feels as though Valentina could be Lidia’s younger self, that Lidia is viewing her past – or the memory of her youth held not just by herself but by Giovanni – as her own competition. Their respective positions on the staircase (symbolising life’s journey) furthers this read. Later, again from an elevated advantage, Lidia witnesses Giovanni and Valentina kissing. Like Don and Betty this is a couple weighted by often unacknowledged betrayals. Tacit agreements. Lies agreed upon.

While the frivolities and excesses of the party recall Fellini’s seminal socialite satire La Dolce Vita from the year prior (another iconic film starring Mastroianni), the comedown here is quite different. Fellini’s party never really seems to end, only undulating through various winds. For Antonioni, however, events have an undercurrent of anxiety for the future. Like Roger Sterling’s party, there’s a preoccupation with legacy that underpins it all, adding an ineffable tension. A fatality and futility that none of its characters can escape. Valentina becomes the fulcrum of the bristling tension felt between Giovanni and Lidia. Through her the couple roil and agitate as Antonio expresses the insatiable dissatisfaction of high society.

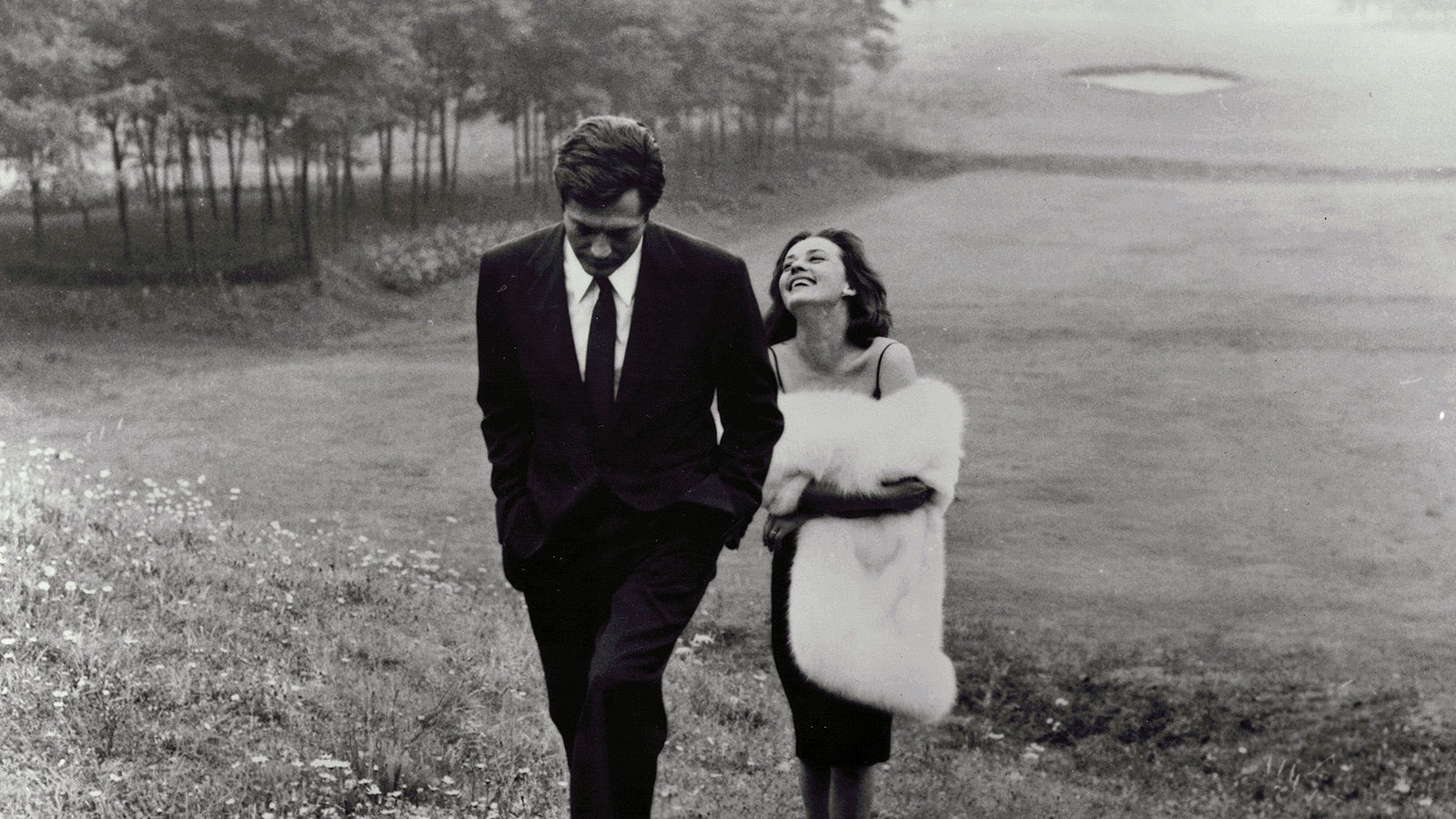

Like the aforementioned Mad Men episode, it ends with its central couple alone at the end of the party, here on the rolling fairway of a golf course, isolated together like the last two people on Earth. But where Betty and Don share an uncharacteristic moment of intimacy with one another, Lidia and Giovanni are resigned, contemplative. Lidia tries to dismiss her husband, indulging suicidal ideation, denouncing her love for him, but Giovanni is patient and persistent. A shot of Lidia from his perspective as they sit with their feet in a sand trap is breathtakingly personal, redolent of this golden era of experimentation in then-contemporary European cinema. Godardian.

Ultimately, Giovanni’s embrace of Lidia against her protestations – and her animalistic acceptance of it – bring La Notte to a conclusion that feels violent. Almost the antithesis of Betty and Don. Yet it’s clear, to me at any rate, that “My Old Kentucky Home” is structurally modelled on La Notte. An appreciating artist’s simile. Antonioni’s finale feels like a kind of desperate personal apocalypse between Giovanni and Lidia. They have no next instalment to place it into context. Their existence ends when the movie ends.

La Notte feels like an exquisite, drowsy, forlorn Last Night on Earth. As Milan ruthlessly tears down the old to replace with the new (also a theme in Mad Men‘s third season), what are these bourgeoisie relics left with? Dinosaurs of another time in the midst of a century of relentless change, the best they can do is paw urgently at one another as we leave them to their doom.

*more of a quartet of films if you include 1964’s impeccable jump to colour Red Desert, which I wholeheartedly do