Director: Lois Patiño

Stars: Amid Keomany, Simone Milavanh, Juwairiya Idrisa Uwesu

Renowned master of Thai slow-cinema Apichatpong ‘Joe’ Weerasethakul famously doesn’t mind too much if audiences fall asleep in his films. He gets it. They’re unhurried, tranquil, zen-like experiences a lot of the time, usually cloaked in the hushed sonic reveries of the natural world. They’re twilight missives that exist in the mezzanines between waking and sleeping. That’s their habitat. Their environment.

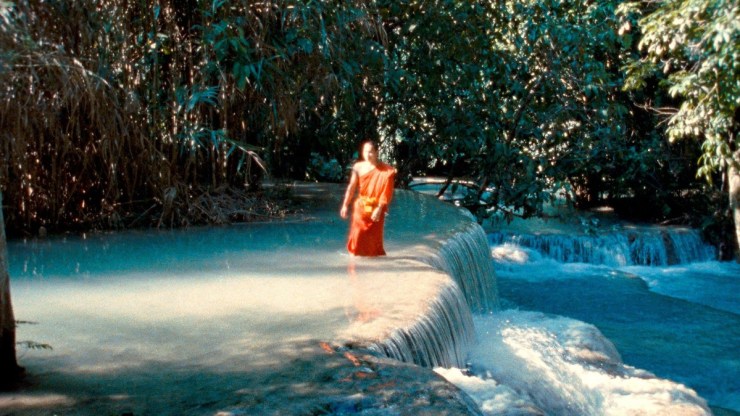

One might well imagine Spain’s Lois Patiño being of a similar mind. Certainly the opening 40-50 minutes of his latest work – the quietly experimental Samsara (not to be confused with Ron Fricke’s National Geographic collage of the same name from a decade ago) – exudes an aura that feels wholesale borrowed from dear Joe. Instead of Thailand, we’re in neighbouring Laos, and in the company of a collective of young Buddhist monks. Again, like Joe’s work, Patiño appears here to favour non-actors, and the languid coverage has a documentary feel. Shot on gorgeous 16mm, it has the quality of a home movie or travelogue.

Ostensibly we get to know a little of the life of a kind young man named Amid (Amid Keomany), who is taking an interest in Tibetan studies and who helps an elderly woman named Mon (Simone Milavanh) to read from Bardo Thodol – the Tibetan Book of the Dead – as she prepares to transition to her next life. Sleepily she recalls dreams of another existence as a red starfish afloat in an ocean. The gentleness of Samsara is so lulling, so unassuming, that one might be ill-prepared for the radical jump Patiño has in store for us.

On screen text advises us that we’re to journey with Mon across the gossamer realms of the Bardo and into her next life. We’re also told to close our eyes for the trip. Cinema has lulled us to sleep before. Has it asked us to die and be reborn quite like this before? Even Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives didn’t invite us on as imaginative and subjective a journey as this, and its a baller move for any filmmaker to ask cinemagoers to shut their eyes for what is promised to be a “long journey”, trusting us to know when to reemerge on the other side somewhere between 10 and 15 minutes later. In the cavernous space between the film’s two halves is an abyss of sounds and the staccato painting of images on the inside of our eyelids via undulating strobe effects. Peep and you’ll risk being bombarded like Gaspar Noé’s in charge of the lighting desk at a new age festival.

In the aftermath of this trip – which feels akin to crossing between mountains in the seamless second half of Bi Gan’s Long Day’s Journey into Night – we emerge on the beaches of Zanzibar and follow the nominal adventures of Neema the goat, whom we are to understand is the transformed Mon (though exposition or conventional narrative storytelling aren’t really ideas one would associate with Samsara). We take in the local atmosphere at the tempo of the rolling tide, learning about seaweed refinement along the way, and capturing something of the spirit of childlike play thanks to Neema’s owner, a young Muslim girl named Juwairiya (Juwairiya Idrisa Uwesu). A red starfish is found in a rockpool. We’re moved to ponder, might this be Mon? Might it be Mon also?

The freedom to roam and ruminate exists all through Samsara. It’s both an art film, an experimental film, and a participatory meditation session. Patiño prompts us to engage with his work in a non-linear, non-cinematic (in terms of blah conventions) yet exceedingly-cinematic manner. It has the most basic of structure but, within its two halves and even during the chasm of its daring middle, there’s a formlessness and fluidity that encourages on-the-spot enquiry, even daydreaming. It is a tapestry; a canvas where we can bring as much or as little as we like. Those who favour cynicism might find the more meandering sections frustrating, but the looseness is half the point.

When talking about the choice to award Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives the Palme d’Or at the 2010 Cannes Film Festive, jury chair Tim Burton praised the work for allowing him to “see things you don’t usually see”. The cynic in me wondered to what degree Patiño is trading on western intoxication with the ‘exoticism’ of South Asia (or Africa, for that matter) to sell something deemed tastefully experimental and adventurous. But the more hopeful, optimistic, credulous side of me imagines Patiño simply swept up in the act of sharing this quiet, lightly playful and arguably radical poem of a film with us.

My Buddhist philosophy is a little rusty, even after this delicate refresher course, but my understanding is that there is some nominal hierarchy imprinted on the natural world, and that Mon’s urge to be reincarnated as a goat, a starfish or other such ‘lesser’ animal would be considered a step backward, which might well explain the disquieting symbolism of the film’s lonesome finale. Even if I’m miles off base on that, the mechanism of the film is designed to leave you pondering, to have you exiting back into the world in a transportive and adventurous state of mind.

Even with your eyes closed, it’s something you don’t usually see.