Year: 1975

Director: Russ Meyer

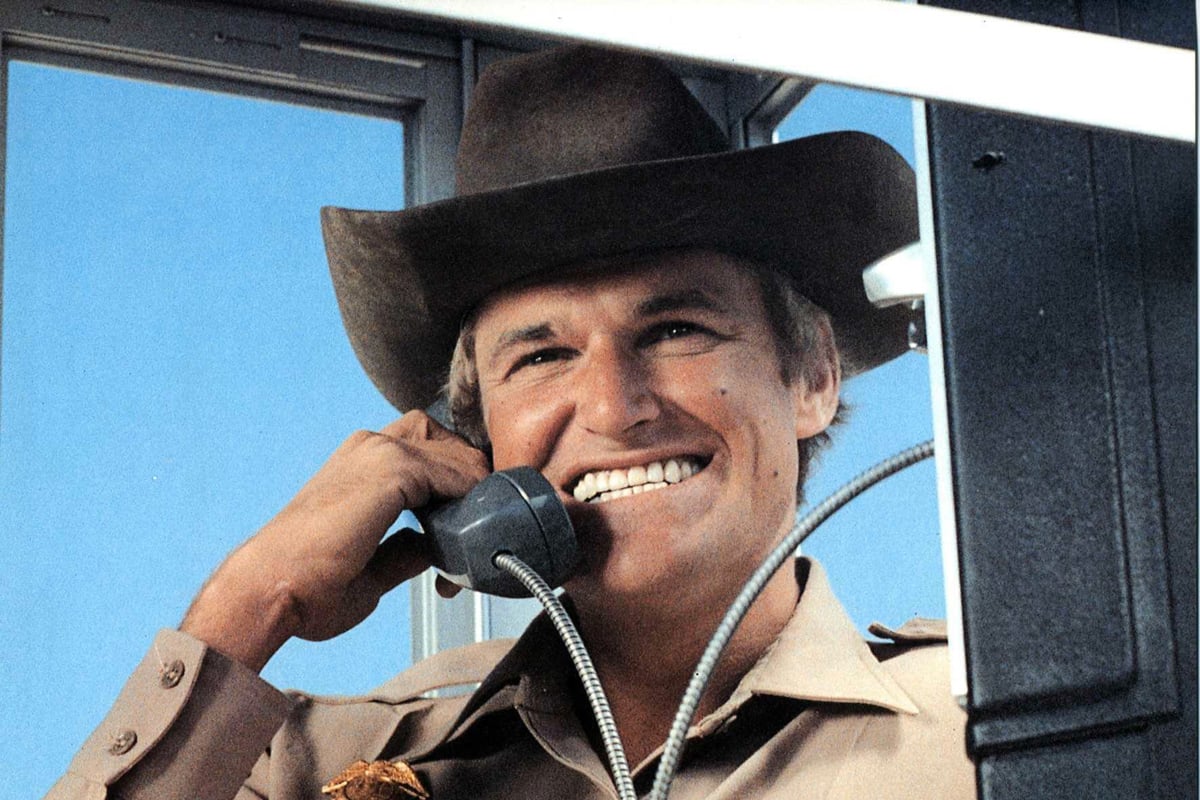

Stars: Shari Eubank, Charles Napier, Charles Pitts

By 1970 Russ Meyer had made it. After over a decade as a huckster, barking orders across nudie cutie and roughie film sets like a drill sergeant and making a name for himself with his pneumatic brand of skin pictures, he’d improbably hit the big time. The impressive box office of 1968’s Vixen caught the attention of the execs over at 20th Century Fox; a studio then in decline following a number of notable bombs. Eager/desperate for a reversal of fortune, they followed the money, giving Meyer and his screenwriting friend Roget Ebert carte blanche to make whatever they wanted, so long as it came in on budget. The resulting film, Beyond the Valley of the Dolls, stands as one of the weirdest studio pictures ever made… but that’s another story.

Trouble was, where could Meyer go from there? All-but hogtied into a rather staid courtroom drama, The Seven Minutes, Meyer’s dalliance with Hollywood was short-lived. He was released from contract and sent back into the wilds. Worse still, his return to independent enterprises faltered. 1973’s ill-conceived slave trade exploitation flick Black Snake lacked his trademark gusto, and managed to offend pretty much all those unfortunate enough to find it. A major rethink was in order.

This coincided with his tempestuous divorce from Valley star Edy Williams, an embittered battle of wills – sometimes public – that strained and skewed Meyer’s already complicated view of women. His films had persistently tried to square a circle born of sex and violence. His next project would take these twin concerns to fever pitch; an hysterical double-down on everything that made Meyer’s films both sexy and scary. His nastiest work was about to burst out.

1975’s SuperVixens is an ugly, ugly picture. Low rent, low budget, epic and furious. Meyer returned to the arid desert locales of his mid ’60s cycle, going back to his roots, but imbued a typically threadbare narrative with a kind of hostility that previously felt just-about contained. Here it overflows. It goes something like this.

Clint (Charles Pitts) is an ineffectual double-denim-wearing gas station attendant in trouble with his jealous partner SuperAngel (Shari Eubank). Things take a dark turn, however, when roaming sadist Harry Sledge (Charles Napier) attacks and murders SuperAngel in the pair’s bathtub (easily the most unpleasant sequence in any Meyer movie). Implicated for the crime, Clint absconds across the Arizona scrubland, bouncing from sexpolit to sexploit with all manner of buxom SuperWomen along the way.

Sitting in the editing room himself, Meyer cuts the assembled footage to a fevered pace beyond even his own previous, frenetic standards. Meyer has multiple signatures beyond his penchant for improbably big boobs. The falling-down-drunk staggering cadence of his edits are among them. SuperVixens transfers his inner sense of agitation via this restlessness. “Too much for one picture!” the tagline promised over Uschi Digard’s gargantuan melons. But it’s the editing that feels barely contained, emblematic of the throbbing violence happening on and off screen.

Meyer discounted notions of auteurism in his work, but SuperVixens can’t help but feel like a product of the world around it. Vietnam was a disaster. The presidency had lost all integrity. Free love had faltered. The world got heavy in the ’70s. SuperVixens‘ ramble through the desert feels like both a rejection of the present and a listless search for something different. Damningly, Clint only ever seems to find more hostility, more jealousy, more rage. Meyer injects his own strangely conservative brand of comedy into proceedings, but the overriding sense is not so much a road to hell as a road to nowhere.

Still, for all the film’s scorched sense of fury, it’s a propulsive and absurdist hoot. Clint’s encounter with Digard’s sexpot farmer’s wife SuperSoul allows room for Meyer regular Stuart Lancaster as her haggard, dungaree-sporting husband, and here SuperVixens tilts most broadly to the popular sex comedies of the era. Right after this Clint falls in with Black deaf-mute SuperEula (Deborah Maguire), who likes nothing more than bouncing around topless on her dune buggy. Not one to entirely mess with his own formula, Meyer swaps out a jealous husband for a jealous father and the pattern repeats itself for poor Clint. But here’s to Meyer for embracing some more positive representation, at least.

Enhancing the sense that Clint isn’t getting anywhere is the inexplicable return of SuperAngel at the end of the picture. This happened, simply, because one of Meyer’s top-heavy starlets pulled out at the last minute, leaving him in a bind. The requisite scenes that hastily explained SuperAngel’s phoenix-like resurrection mostly hit the cutting room floor, making her return even more mystifying, but if she is – keep a straight face, now – Meyer’s vision of Christ, her figure is more than fitting for his no-doubt prurient vision of what the almighty might look like. Clint is his mesmerised, amnesiac proxy.

Charles Pitts is admittedly quite bland, exhibiting limited range. But Napier is another story. Sledge is almost as vivid and vile a villain as Dennis Hopper’s Frank Booth from Blue Velvet, and Napier leans into the nastiness. Intriguingly one might argue he stands in for Meyer’s own documented homophobia. Sledge self-describes as being “built like a brick shithouse” and enjoys listing off his physical endowments. His broad-chested menace feels like Meyer wrestling with his own feelings about men. As elsewhere, SuperVixens plays like an unfiltered exposé of Meyer’s subconscious. The film ends – unsurprisingly – in a frenzy, with Sledge raining sticks of dynamite down on Clint while SuperAngel sits nude and perilous atop a jagged rocky outcrop. Sledge accidentally detonates himself, Clint and SuperAngel finally screw and the credits roll.

Things would only get more intense in the remaining two pictures of Meyer’s career, reaching a slapstick peak with 1979’s Beneath the Valley of the UltraVixens. Meyer would continue upping the ante, speeding up those edits, skirting around the hardcore antics that had come to define the movies playing drive-ins and grindhouses. Seeing himself above all that, Meyer was simply pushed out of the business by his explicit competitors, or else tarred with the same brush by conservative cinema chains. The game had changed and his incredible run was over.

Let’s not get too carried away. His one true masterpiece is Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! from 1965 (already covered in this series). SuperVixens is more of a personal favourite, and hard-won at that (it’s a title that’s grown on me slowly over many years). But I am drawn back over and over. So too, briefly, were Meyer’s missing punters. If Meyer’s picture inadvertently laid bare his own concerns of inadequacy, the box office (temporarily) kept him hard. Personally I’m here for the anarchic sense of a lurid cartoon come to life that just doesn’t exist with this kind of warped sincerity in the modern cinematic landscape.

That may well be an evolution for the good, and I’m certainly not excusing Meyer’s legendary disregard for wellbeing and safety on his sets. Meyer the Monster is well documented (though he outlawed copulating behind the scenes; his was a more militant variety of ‘professionalism’). But this is an unvarnished time capsule, hysterical and full to bursting. Pure id and weirdly brave for it. Meyer didn’t need a shrink; he had a cine-camera, and we were all somehow allowed to bare witness.

As wholesome and sanitary as a backwater service station bathroom.